Monday morning, I sat at the table with my daughter and a hot cup of coffee, gripping my eyes tight to hide my tears from her. All the positivity from my weekend evaporated; today’s high temperature was predicted to be 103 degrees. This bizarre heat wave is the future we’ve been warned about.

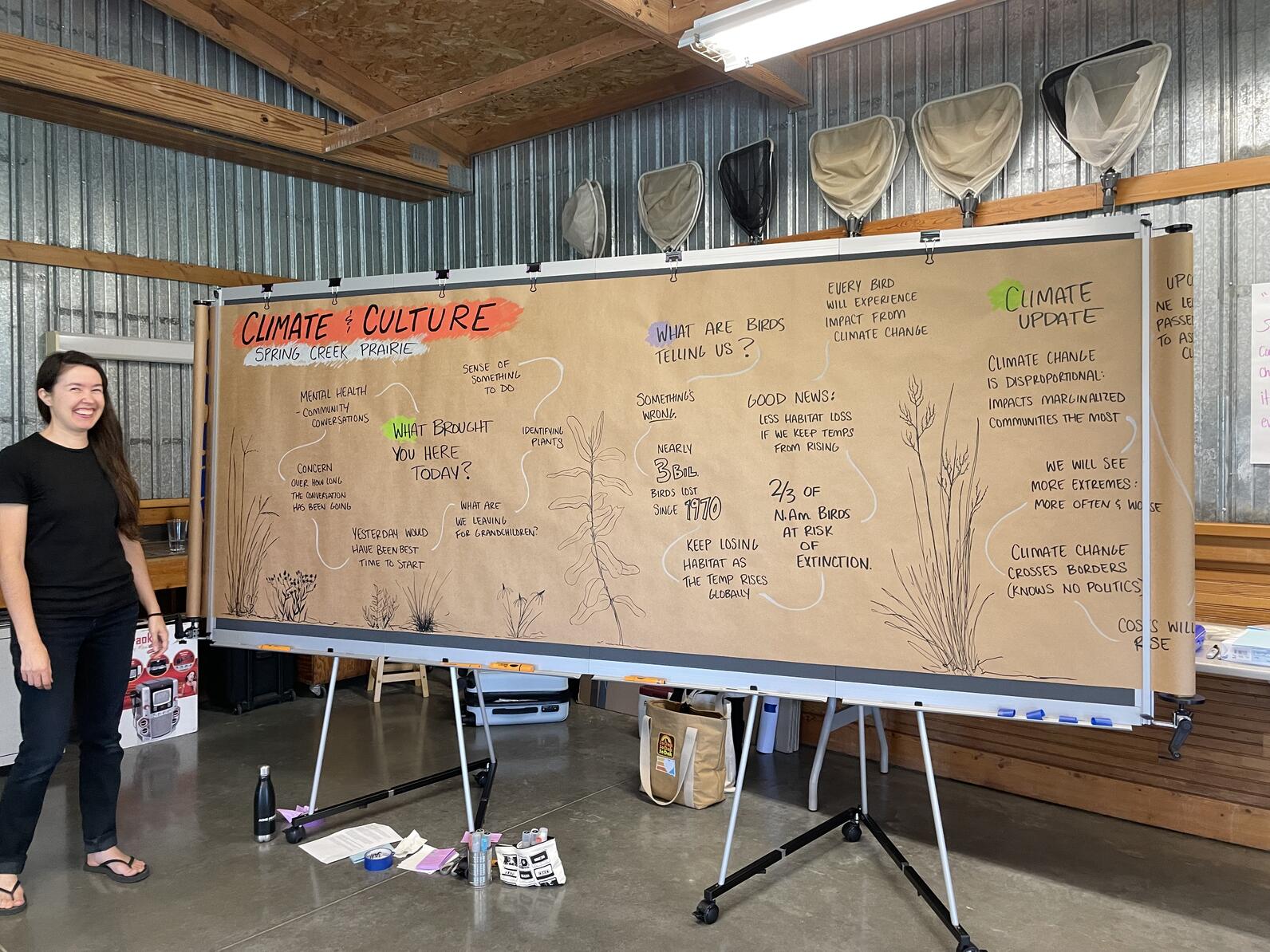

The day before, at the Climate and Culture conservation at Spring Creek Prairie, participants were asked why they were there: climate anxiety was one recurring answer. Multiple panelists at the event stressed that they have noticed an increase in climate anxiety, marked by feelings of fear, grief, and hopelessness around both the future of the world and their own personal future. Participating educators talked about how to navigate this in age-appropriate ways. But panelists stressed that these emotions are powering a major cultural movement.

Martha Durr, Nebraska State Climatologist, discussed a palpable shift after the devastating floods in 2019, not just from those directly affected but also from rural and agricultural communities. “The tone and the questioning was suddenly very different. It was ‘are we going to get more of these floods?’ and ‘What about solutions?’...the level of concern in some people who didn’t want to address climate change has now shifted into talking through solutions.”

“People are understanding that we can’t just continue to do what we’ve always done,” added Kristen Eggerling. “We have these great ideas, but we have to make them feasible for everyone.”

Kristen and Todd Eggerling are neighbors of SCPAC who farm and graze cattle on property that has been in Kristen’s family as far back as 1873. Farmers and ranchers, she said, have to be creative and respond to conditions throughout the growing season. But politicians and decision-makers seem to be too risk-averse to explore that kind of creativity with sustainability solutions.

“Can we value a green lawn less, because we don’t have the water to sustain it?” Eggerling said. “And in agriculture it’s that same thing: do you value raising a particular crop because that’s what you’ve always done or because that’s what we have the knowledge to do or do we look at other options, can we look at other ways.”

There are significant financial barriers for farmers and ranchers who might want to use new technology, but there are also really basic infrastructure problems, like whether new electric vehicles can handle narrow dirt roads. Just as we need to tackle climate change on global and individual scales, many of the solutions communities are trying are a child of new technology and a return to the ways of the past.

Colleen New Holy, a member of Oglala Sioux Tribe, talked about her community in Pine Ridge building generational homes with solar and passive design to withstand extreme conditions and end reliance on the external power grid. She calls this development “a reconstruction of our past.”

“We understand that there is no permanence, and I think that has to be a major collective switch with the older generations,” New Holy said. “Development can happen, I think it just needs to be handled in a thoughtful way where your ultimate goal is that you’re not building something that permanently affects the environment.”

Later, in small group discussions, Renée Sans Souci, a member of the Omaha tribe of Nebraska, talked about the recent dedication of Chief Big Elk memorial at Omaha’s Lewis and Clark Landing. Inscribed beneath the statue are words from his prophetic ‘Great Flood Speech.’ Sans Souci, speaking with measured words, told us that the Chief’s message was about survival: adapt in order to survive.

I felt grief in that word, ‘adapt,’ signifying all we have lost and all we have to lose. But we must adapt: change our habits, change our energy systems and economy, and change the way we relate to the natural world.

Kim Morrow, Lincoln’s Chief Conservation Officer, talked about effecting change on multiple scales. “The city of Lincoln adopted its climate action plan in 2021. We are the first city in the state to have one...That plan has been enormously helpful laying out a roadmap for us to achieve our goal of reducing our emissions by 80% in 2025. Our electric utility, Lincoln Electric System, has a goal of becoming net zero emissions by 2040. LES has already reduced their emissions by 36% since 2010.”

The city of Omaha and Nebraska Department of Energy and Environment have both received federal grants to develop climate action plans – 46/50 states will be initiating a climate plan with funds provided by the IRA.

I know I’m not the only person who feels the weight of upheaval – 2019 and 2020 was a barrage of successive disasters that re-directed my life. But I have reconstructed a life centered on what I value: my family, independence and self-reliance, a close community, a job I believe has positive impact. And, yes, a yard full of native plants over grass. The tide is changing.

---

Climate and Culture: a Conservation was organized by the Spring Creek Prairie Board and funded by Humanities Nebraska as part of “Weathering Uncertainty” and the Democracy and the Informed Citizen initiative administered by the Federation of State Humanities Councils.

Panelists:

- Martha Durr, Nebraska State Climatologist, UNL School of Natural Resources Professor

- Kim Morrow, Chief Sustainability Officer for the city of Lincoln

- Kristen and Todd Eggerling, neighboring farmers

- Colleen New Holy, Member of the Oglala Sioux Tribe

- Judy Greenwald, Former SCPAC Board Member

- Moderated by Jason “The Birdnerd” St. Sauver and Meghan Sittler

- Conversations moderated by Greta Leach of Mission Matters and Jamie Horter